Recently, the Dutch Fiscal Information and Investigation Service (FIOD), together with the help of Eurojust, stopped an enormous VAT fraud scheme, kudos for the work done! The fraudsters defrauded the Dutch tax authority for €9 million between 2017 and 2020.[1] In this blog post we try to reconstruct the VAT fraud scheme. Important to note is that we’re basing our research on publicly available resources only. Therefore, it might be possible that we miss some links within the fraudulent value chain. Still, the reconstruction can serve as an example, because it does include the most critical aspects of the VAT fraud scheme: fraudulent companies not paying VAT. After reconstructing the VAT fraud scheme, we will show how by making use of modern technologies, tax authorities can find these fraudsters in an earlier stage, potentially saving millions of euros.

Missing Trader Intra Community (MTIC) fraud

(You can skip the recap in case you are familiar with the term)

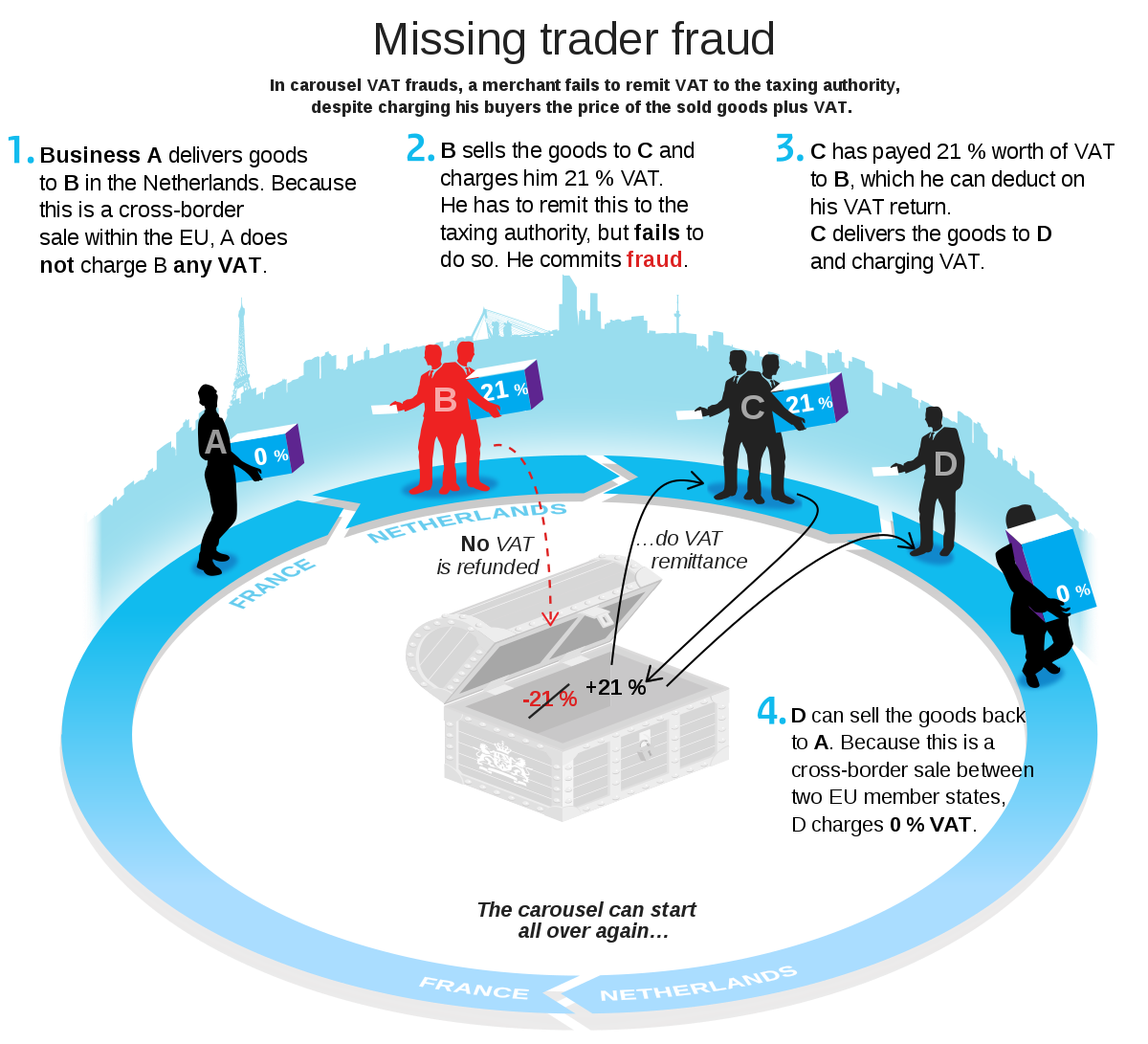

Missing Trader Intra Community (MTIC) is the most common form of VAT fraud in the European Union (EU). In its most simple form, it works as follows. There is one company located in an EU Member State. Let’s take the Netherlands in this example. This Dutch company (Carousel ltd.) sells its goods to a company located in another EU Member State, for example to a German company (Fraudster ltd.). The Dutch company does not have to charge any VAT because it concerns an intra-Community transaction. In general intra-Community transactions are exempted from VAT.[2] The Germany company goes on to sell the same goods to a second company in the Netherlands (Missing ltd.), again not charging VAT. The last step is that Missing ltd. will sell the goods to Carousel ltd.. As it concerns a domestic transaction, Missing ltd. will now charge 21% VAT (Dutch VAT rate). Carousel ltd. will pay this VAT to Missing ltd, but Missing ltd. will not pay this VAT to the tax authority. Now the scheme can start over again, that’s why such a scheme is also called a carousel fraud scheme.

In this scheme Missing ltd. is the Missing Trader. The Missing Trader is the company that is actually pocketing the VAT by not paying it to the tax authority as it should, thus committing VAT fraud. This is the most simple form of VAT fraud. Fraudsters can involve multiple other companies in the scheme to make it more complex (as is done in Figure 1). This could even include honest companies that are not aware of being involved in the fraudulent value chain.

Figure 1: a Missing Trader Intra-Community Fraud scheme

Source: Dutch Tax Authority

€9 million VAT fraud by trading SD carts

Let’s now have a look at a real-life example of carousel fraud. The FIOD discovered a network of traders that in total defrauded the Dutch tax authorities for €9 million. The scheme that was set up by the network is way more complex than the example given above, so bear with us.

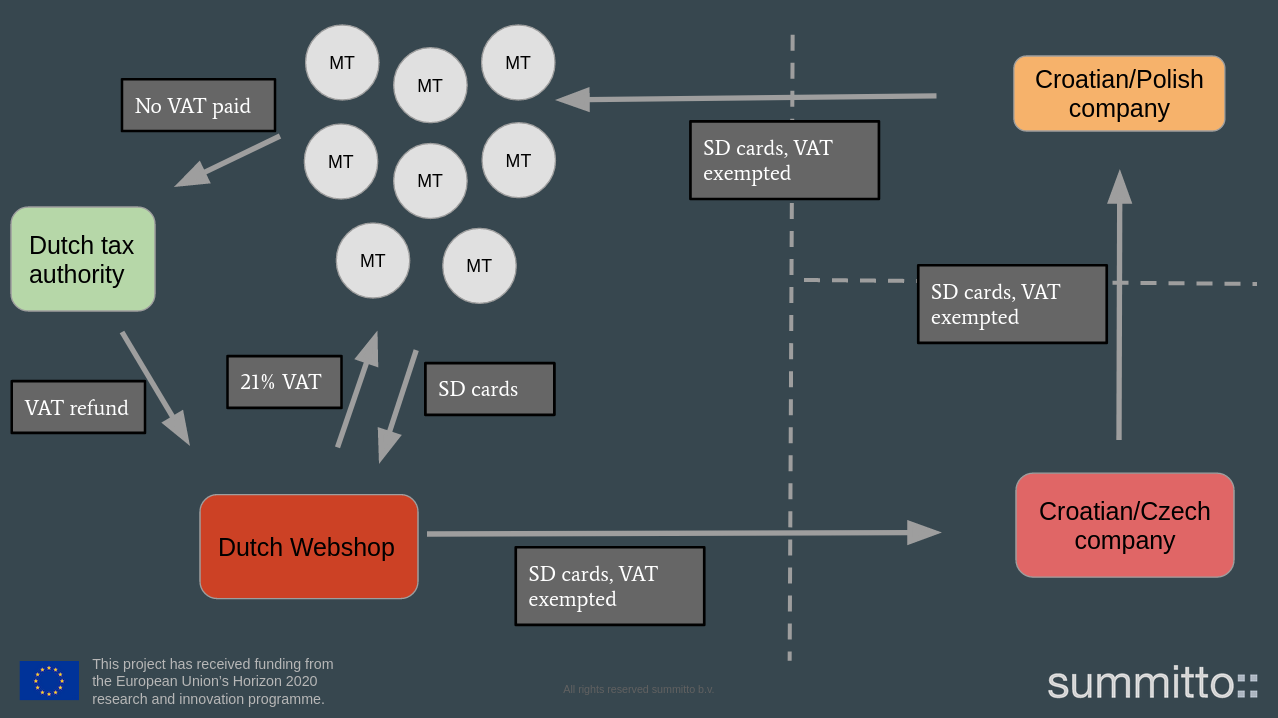

The criminal network set up a complex carousel fraud scheme by using a web company that sold mobile phones and tablets.[3] This webshop (and potentially other companies that were not mentioned in the sources we had access to), bought SD cards with VAT from Dutch companies that were later identified as Missing Traders by the FIOD. These Missing Traders cashed the VAT and did not pay it to the tax authority. Afterwards, the same goods were sold to companies in Croatia and the Czech Republic without having to pay VAT because intra-Community transactions are exempted from VAT. Conduit[4] companies located in Croatia and Poland were then used to sell the goods back to the Missing Traders in the Netherlands. From there on, the carousel could start again.

The criminal group leading the network also put so-called buffer companies in the value chain to hide the fact that the value chain is fraudulent. These buffer companies only pay VAT of a small margin made from the transactions. The FIOD suspects that there were at least 8 Missing Traders involved in the complete scheme, showing how complex these schemes can become.[5]

In Figure 2 we’ve tried to reconstruct the entire scheme. Even when leaving out the buffer companies, it is already a very complex value chain. No wonder that it’s hard to find these fraudsters.

Figure 2: Reconstruction of the SD card VAT fraud scheme

Source: summitto

How can real-time reporting help to reduce VAT fraud

The main problem of such fraud schemes is that tax authorities and the FIOD don’t have the tools to check if the VAT return of those fraudsters actually corresponds to the VAT that is stated on the invoices that were sent to (in this case) the webshop. So, if it wasn’t for the excellent work of the FIOD, conducting extensive research, the scheme would never have been revealed in the first place.

A tool that can offer these checks in an automated fashion is real-time reporting. We have explained the concept of real-time reporting in more detail here, but the key of such a system is that companies send their invoices to the tax authority so that they can conduct (automated) checks. These checks will reduce the detection time from years (this particular scheme lasted 3 years) to weeks or at most a couple of months. Reporting invoices will make it easier to detect fraudsters because, as stipulated by VAT professor Redmar Wolf “payments are traced by following the path of invoices”.[6] A real-time reporting system allows tax authorities to make the VAT returns dependent on the invoices that a company has reported. In other words, with real-time reporting there will no longer be the freedom to report any amount of VAT you want. Additionally, the VAT return of the buyer can be linked with the VAT return of the supplier. This creates a self-controlling mechanism as the buyer wants to make sure that the supplier is reporting its invoice in a correct manner, because it affects his/her own VAT refund.

Furthermore, real-time reporting, if implemented properly, will prevent the situation where companies that end up in a fraudulent value chain have to defend themselves in front of a court to prove that they ‘did not know or could not have known’ that they were involved in the VAT fraud scheme. They can then simply point to the fact that they have reported their invoices to the tax authority. Real-time reporting has successfully been implemented in many countries all over the world, but only since the last couple of years it also reached EU Member States. For example, Italy implemented such a system in 2017 and managed to decrease their annual VAT Gap by €4 billion.[7]

One essential downside of existing real-time reporting solutions is that they store all data in a centralised location, where relevant officials often have access to that data in plain text for analytical purposes and this data ends up to be in a silo only for the Tax Administration to be used. To overcome this problem, summitto developed a real-time reporting system that does not store any actual data, but only encrypted fingerprints. Furthermore, these encrypted fingerprints can be made publicly available, creating additional benefits for businesses. Namely, businesses can provide mathematical proof that they used their invoices for VAT purposes, allowing them to e.g. automate audits.

In case you want to learn more about how summitto’s real-time reporting system exactly works and how it benefits both the public and private sector click here. For questions, shoot us a message at info@summitto.com

[1] https://www.fiod.nl/onderzoek-naar-miljoenenfraude-met-btw/

[2] https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/vat/eu-vat-rules-topic/exemptions_en

[3] https://www.eurojust.europa.eu/major-vat-scam-memory-cards-halted-netherlands

[4] https://definitions.uslegal.com/c/conduit-company/