Introduction

China’s share in the world economy and political influence has been steadily growing since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms at the end of the 70’s. The liberalisation of the Chinese economy required additional revenue for the state. As one of the tools, China introduced VAT in 1984. Ten years later, the Chinese government developed a nationwide value-added tax administration and monitoring system, better known as the Golden Tax System (GTS).

The aim of this blogpost is to develop a better understanding of the Chinese GTS and to highlight the differences to European reporting systems and TX++. For this, we will first analyse the history and functioning of the Chinese system while in a second part we will compare it to other systems.

The Golden Tax System

Before explaining the functioning of the GTS, it is important to first focus on the Chinese VAT system. China has a unique VAT system which applies also to most financial services. Businesses in China are divided into two categories: general VAT taxpayers and small scale taxpayers.

Small scale taxpayers are businesses with an annual VAT taxable revenue of less than RMB 5 million (equivalent to USD 800,000). VAT rates being based on the type of issuer and not on the product compared to EU VAT systems, the maximum VAT rate applied to small scale taxpayers is 3%. Nevertheless, small scale taxpayers are not allowed to deduct input VAT. General VAT taxpayers on the other hand are businesses with a VAT taxable revenue above RMB 5 million and are charged a maximum VAT rate of 13%. These businesses can deduct input VAT and must adhere to the Golden Tax System[1], the Chinese invoice reporting system, in order to deduct input VAT.

Many of us might wonder why the Chinese invoice reporting system was given the name of Golden Tax System. This name refers to the high value of the invoice information, comparable to gold, being VAT the main source of revenue for the Chinese state.[2] This also creates a direct link to the official colours of China: red and yellow/gold.

The Golden Tax System is a nationwide VAT monitoring system that was introduced in 1994. The GTS uses the online network of the Chinese tax authorities to closely control VAT special invoices issued by general VAT taxpayers. These invoices are known as fapiao[3] and are officially issued on paper and administered by the Chinese State Taxation Administration (STA). VAT taxpayers need to purchase fapiaos at their local tax boroughs[4], effectively meaning that businesses have to pay taxes before conducting sales. This system has a direct influence on the cash flow of Chinese companies and is a clear difference from the European VAT system where every tax has to be paid at the end of a period.

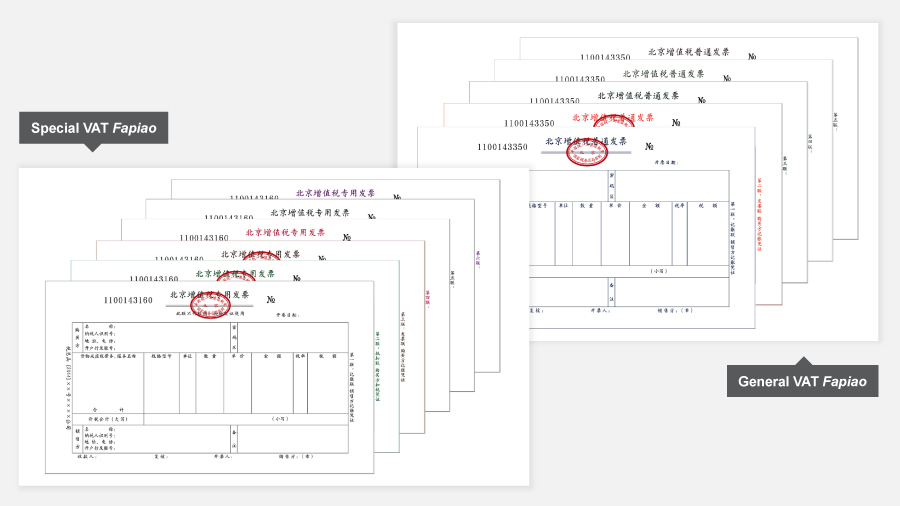

Fapiao can mainly be sorted into two categories – general VAT fapiao and special VAT fapiao. While the special VAT fapiao is only meant for taxpayers that are obliged to report to the GTS, general VAT fapiao can be used by any company registered in China but has no value for VAT deduction purposes.

Figure 1: Special and General VAT fapiao

Source: China Briefing[5]

Every fapiao is issued with a special and unique code. To be valid, the fapiao needs to be registered in the network of the national tax authorities when performing a transaction.[6] Every VAT liable business must therefore purchase the official software of the tax authority in order to register the invoice after its issuance. Only the invoices bought directly from the tax authority and registered in its network are legally valid.

Gradually, the fapiao will change its form from paper to electronic. In 2020, the electronic special VAT invoices pilot program had been trialled in a few Chinese cities with the purpose of expanding it to all taxpayers in 2021. The reform has been delayed because of the spreading of the Covid-19 pandemic but already 11 out of 34 Chinese provinces make use of mandatory e-invoicing.[7]

The main difference between paper and electronic fapiao is the e-signature which is replacing the stamp on a paper-based invoice. E-invoices issued by taxpayers are verified through authorised companies. Currently, only two companies are allowed to act as trusted third party service providers and therefore every e-fapiao must be validated by those two companies exclusively. However, the transfer of the invoice from the supplier to the buyer is less regulated and can happen via email, QR code or other methods decided by the contractors.[8]

The Golden Tax System in comparison to TX++

The Chinese Golden Tax System is very unique in comparison to implemented real-time reporting systems around the world. Its main peculiarities reside in the fact that taxpayers are required to pay taxes before the transactions, when they purchase fapiao from the tax authority.[9] It is assumable, that the Chinese Golden Tax System is one of the most regulated in terms of requirements, and therefore also of compliance costs. No other system with similar stringent requirements is implemented at the moment.

In Europe, the Italian SDI system might still be quite burdensome for businesses in terms of data shared with the tax authority and centralisation. Although every invoice must transit through a centralised database run by the Italian tax authority, companies still have the possibility to opt for a variety of third party service providers.[10] Furthermore, by allowing companies to pay every tax due at the end of a period (sometimes even quarterly) the cash flow of businesses is positively affected by the national VAT system.

Even more liberal is TX++, as it does not collect any invoice information. By making use of the most modern cryptographic technology, TX++ is able to detect VAT fraud in a confidential way, lowering the burden on businesses and reducing the risk of cyberattacks. By allowing the use of different invoice standards and being compatible with existing EDI systems, TX++ provides a high level of freedom to its users while still reducing the VAT gap.[11]

Conclusion

The Chinese Golden Tax System is a remarkable example of a real-time reporting system. The Chinese government opted for a fully centralised and regulated solution, which has a considerable impact on the way of doing business in China. This system may have its perks in a society which is already quite regulated, but would not be suitable for European standards. European countries rather need a solution which has a lower impact on businesses and protects its confidentiality. Such a solution exists and is called TX++.

In case you want to know more about our periodic or real-time reporting solutions have a look at our website at www.summitto.com or do not hesitate to contact us at info@summitto.com

[1] https://www.sjgrand.cn/vat-payers-in-china-small-vs-general-taxpayers/

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I2LuPebIp_s

[3] https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-golden-tax-system-phase-iv-an-explainer/

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I2LuPebIp_s

[5] https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-e-fapiao-system-at-a-glance/

[6] https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-golden-tax-system-phase-iv-an-explainer/

[7] https://www.pagero.com/compliance/world-map/china/

[8] https://www.pagero.com/compliance/world-map/china/

[9] Also in some European countries in the last century VAT had to be paid before the transaction. This was made possible through stamps. Taxpayers had to buy stamps in the amount of the VAT to be paid and add them to the invoice. Today, this is not the case anymore. see e.g.: https://winterstamps.nl/filatelie/voorbeelden/btw-betalen-leuk/

[10] https://www.agenziaentrate.gov.it/portale/web/english/electronic-invoicing